Sponsored Content

What could drive global inflation materially higher this year? Output gaps in the US, Eurozone and Japan are apparently closed, yet there is justifiable scepticism about the extent of persistent inflationary tailwinds. For example, although unemployment in the US has been below 5% since early 2016, growth in payroll wages has been a subdued 2.5%. In the last month this jumped to a cyclical high of 2.9% but this figure is low in comparison with the previous economic cycle. Meanwhile, continued robust job creation implies that there is still some slack in the US economy, even today.

Tentatively, this suggests a ‘new normal’ has emerged in the US – economic output and employment growth need to run above trend, for many months, in order to generate even incipient signs of underlying inflationary pressures. Yet, wage growth in the Eurozone and Japan remains considerably lower than in the US and surveyed inflation expectations remain well anchored.

Will the recent rise in global equity and commodity prices lift underlying inflation across the US, the Eurozone or Japan? Some scepticism is justified. An immediate question is: what degree of monetary policy tightening is required when inflation is close to target but there are few signs of it accelerating. Irrespective of any policy tightening by the G3 central banks in the year ahead, nominal yields are likely to rise, with real yields following. This illustrates the tension between, on the one hand, a maturing global cyclical upswing and the imminent end to global monetary policy easing, and on the other, those economies, such as the Eurozone, where inflation is currently low, and a premature tightening in financial conditions could make desired policy normalisation very difficult.

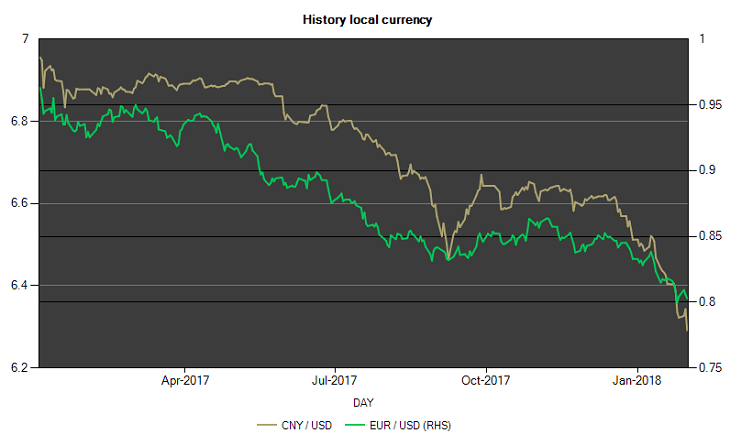

Figure 1: US dollar vs Chinese renminbi and euro

source: Cameron Hume, CaTo