There is an old story that says if you put a frog into boiling water it will jump out but if you place a frog in cold water and heat it slowly to boiling point the frog won’t jump out but rather be boiled alive. The analogy has been made to bond market investors that have watched yields plummet lower and lower but are becoming blasé about the risks this represents.

Many investors, traders and economists look to central banks to pull monetary policy levers in order to keep the economy on track. In recent years central banks around the world have taken bond yields along the curve to record lows through a combination of record low official rates at the short end and purchases of government bonds at the long end. Lower interest rates would promote more investment and the effect of higher investment would be to lower unemployment rates and avoid deflation, or so the theory went.

Seven years after the US Fed implemented its zero interest rate policy and quantitative easing policies which have spread to Europe and Japan, doubts are rising as to the effectiveness of these policies. There are now some respected economists who not only think these policies have been futile but indeed will have negative consequences in the future.

Bill Evans, Westpac’s much-respected chief economist now thinks investment has been and will continue to be weak as long as businesses feel long term investment is too risky. “Businesses are concerned about disruption through technology which might quickly render long term investments obsolete; some businesses believe that shareholders will react poorly if they take on new investment which cannot justify something like a 15% return despite the US risk free rate….holding at 1.5%.”

The policy of “quantitative easing” or the purchases of bonds by central banks from bond holders in exchange for cash has forced yields into negative territory in much of Europe and Japan, so much so Mr Evans suspects other bond investors are bidding the price of US bonds up and thereby dragging US yields down. Bond yields go up and down and this is nothing new. What is new the sheer size of central bank purchases and the resultant downward pressure on yields. For example, the Bank of Japan will own all Japanese Government bonds in a few years’ time if it continues purchasing them at the current rate. Central banks are not value buyers and purchases are made at the prevailing market price/yield; value is not a consideration and so it is no wonder yields are close to or are below zero.

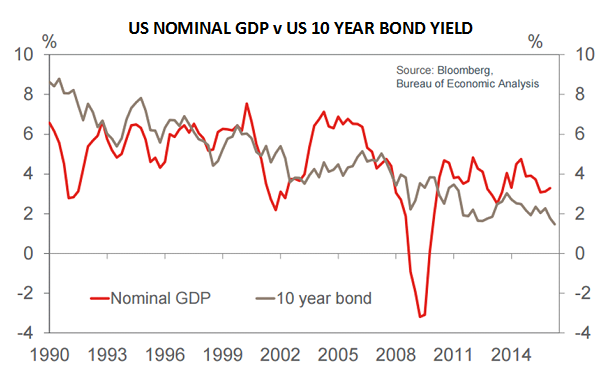

The sting in the tail of all of this central bank largesse comes when central banks finally give up on their unconventional monetary policies. As Mr Evans puts it, “When these QE policies are finally abandoned, as they surely must be, there will be a huge repricing of risk free assets with rates heading in the direction of nominal GDP growth, although the pace of this adjustment will still depend on the other progress which governments have made in closing the savings / investment imbalance.” Nominal US GDP growth and the US 10 year bond yield are shown in the chart below. Readers will see there has been a good correlation between the two and the implication is yield will rise.

For investors in Australian bonds, this means yields will rise. The correlation between yields on US and Australian 10 year bonds is around 90%. “When the US sneezes, everyone else catches a cold” is a saying which is as true as ever. Central banks may currently show little or no signs of ceasing their interference in financial markets and so the temptation is to carry on as usual and expect interest rates to stay low. However, is it now time to ask if we are the frogs being boiled slowly?