Sponsored Content

By guest contributor Stephen Miller, advisor, Grant Samuel Funds Management

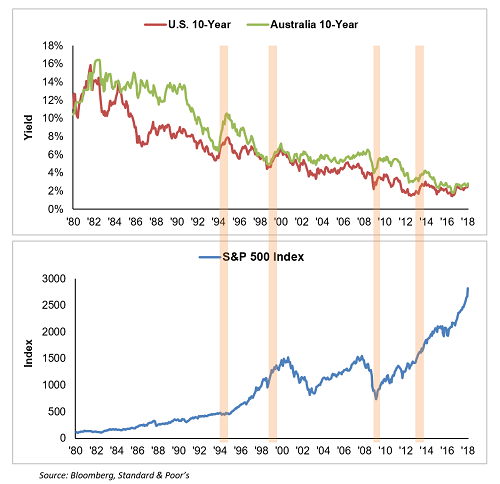

On Friday 4 February 1994, the US Fed under Alan Greenspan tightened monetary policy for the first time in five years. This unleashed the biggest ever calendar year bond sell-off, in basis point (bps) terms, in the US 10-year yield during the approximate 35-year bond bull market that ran from 1982 to 2017.

Although a torrid period, markets did re-commence their long bull run; some years later it reflected the fallout from the Global Financial Crisis and its aftermath – low global growth, deflation risk, a seriously impaired banking system and the attendant ‘unorthodox’ policy response from the major global Central Banks.

It’s an interesting comparison to consider this period in terms of the more recent sell off. What did the S&P500 return in calendar 1994 when US 10-year yields rose around 200 basis points? The index itself fell a modest 1.6% but returned a small positive of around 1.3% after dividends. What about other episodes of rising bond yields?

Context is everything

Chart one: Context is everything

1994: US 10-year yields rose 203 basis points. The S&P 500 returned 1.3%.

1999: US 10-year yields rose 194 basis points. The S&P 500 returned 20.9%.

2009: US 10-year yields rose 121 basis points. The S&P 500 returned 25.9%.

2013: US 10-year yields rose 95 basis points. The S&P 500 returned 32.1%.

The point here is that the relationship between a change in bond yields and the return on equities is not mechanical. Context is everything.

The inflation path (and expectations thereof) are critical

The following chart from Minack Advisors shows bond/equity return correlation is generally negative when inflation is below 3%. Or as Minack Advisors would have it: when “good news is good news”: stronger growth leads to improved corporate earnings and bond yield expectations are contained (because inflation is contained), leading to better stock prices.

When inflation gets toward the 3% level, things become a little more problematic and “good news becomes bad news”: stronger growth may lead to improved corporate earnings, but expectations of even higher bond yields lead to a tipping point for stock prices. This is clearly the key risk in the current environment and an even greater one in 2019. But in my view, it is the risk case, not the central one. It is also exacerbated by higher US budget deficits and Fed balance sheet shrinkage which both lead to more net Treasury bond supply (higher bond yields).