By guest contributor Ken Atchison, Director, Atchison Consultants

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary problem.” So stated economist Milton Friedman. It is a sober lesson being learnt again in Australia. How high will interest rates rise as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) corrects for the excessive stimulus that was launched in the response to the pandemic? Certainly, higher than the latest official rate of 1.85%. Potentially, the peak interest rate could approach the level of the current inflation rate of 6.1%, which would still have investors behind the curve in real terms with inflation projected to peak at 7.75%.

In the pandemic response, interest rates, which were already low, were reduced by the RBA to extraordinarily low levels. Additionally, the RBA applied “quantitative easing” (QE), which involved the RBA buying debt securities, thereby reducing longer term interest rates while government spending increased to extraordinary levels. For the public, their lives were dramatically affected by lockdowns, closed borders and, in the case of Victoria, a curfew.

Not only did the Commonwealth Government increase spending, but the states did so too without any regard for debt servicing. In Victoria, Treasurer Tim Pallas said they were doing what the RBA and Federal Treasury were urging! There was no official acknowledgement that Victorian debt servicing was not a responsibility of the RBA or the Federal Government.

Monetary stimulus through the RBA, when combined with rampant Commonwealth and state government spending, has resulted in very strong economic growth with unemployment at a record low of 3.5%. It has also underpinned rising share and property prices and, finally, inflation. The consequences of stimulus are now being experienced.

As William White, a former chief economist of the Bank for International Settlements, has stated, “Central banks have pursued the wrong policies over the past three decades which have caused ever higher debt and ever greater instability in the financial system”. Government policies applied in response to the pandemic have exacerbated the problem.

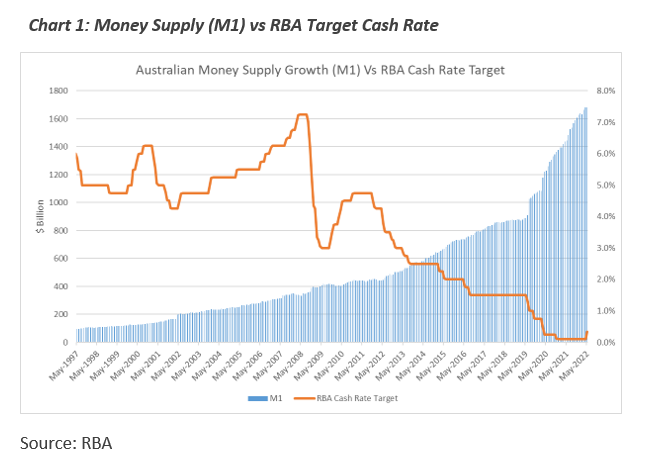

Evidence of the extent of stimulus is provided in the low interest rates and growth of money supply shown in Chart 1.

The money supply grew by 38.1% in the year to May 2020 as the stimulus kicked in. It grew by 17.5% in the year to May 2021 and still very strongly by 16.5% in the year to May 2022. Initially, the money growth flowed into asset prices, as investors reacted to a cash rate of 0.1% to opt for shares and property. In hindsight, considering the extent of the monetary and public spending stimuli, bull markets in equities and property should not have come as a surprise. And the RBA, and governments too, were relaxed about an outcome that was having a positive impact on many people’s lives at a time of enormous social stress.

However, the aggressive stimulus was inevitably going to flow into the broader economy and trigger inflation. Today, it is 6.1% and is projected to rise to 7.75%, a sobering thought when it is considered the RBA’s policy target is for an inflation rate of between 2% and 3%.

Alternative policy options seem limited. Federal Government spending cuts require decisions by a new government that it is unlikely to make for political reasons. Early action by the new Federal Government has been to increase spending. It is also probable that state governments will continue to use debt financing to spend excessively.

Increased interest rates imposed by the RBA will be the immediate policy change that can be implemented with a degree of certainty, albeit with a delayed response time of 12-18 months. The RBA was part of the aggressive stimulus which has led to high inflation. It must acknowledge that the RBA now has sole responsibility for unwinding the stimulus through higher interest rates in the absence of tighter fiscal policies at a federal or state level.

An increase in interest rates by a further 3.5% or more, taking the cash rate above the inflation rate or even higher, will be required to reduce inflation to an acceptable level. When the full economic ramifications of such interest rate moves become apparent via a rapidly slowing economy and falling asset prices, perhaps governments will finally become more fiscally responsible.