Summary

The latest US nonfarm payroll report came in far below expectations, with August job growth at just 22,000. This weaker-than-expected figure has once again drawn market attention to the state of the US economy. With the Federal Reserve’s rate cut now imminent, how should we track the labour market—and what exactly is this so-called “fragile balance”?

Two Labour Market Indicators To Know

To understand how the labour market functions, we need to look at both demand and supply:

- Nonfarm Payrolls (Demand Side): Reported monthly by the US Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS), this data tracks changes in employment based on business surveys. It covers all sectors except agriculture, private household employees, the military, and nonprofit organisations.

- Labour Force Participation (Supply Side): Based on the US Current Population Survey (CPS), this measures the number of people participating in the labour market. It includes those currently employed, actively seeking jobs, or willing to work but unable to find employment.

Together, these two metrics give us the structure of the labour market: nonfarm payrolls reflect business demand for labour, while labour force participation reflects household labour supply. Analysing them in tandem allows us to better understand current labour market conditions.

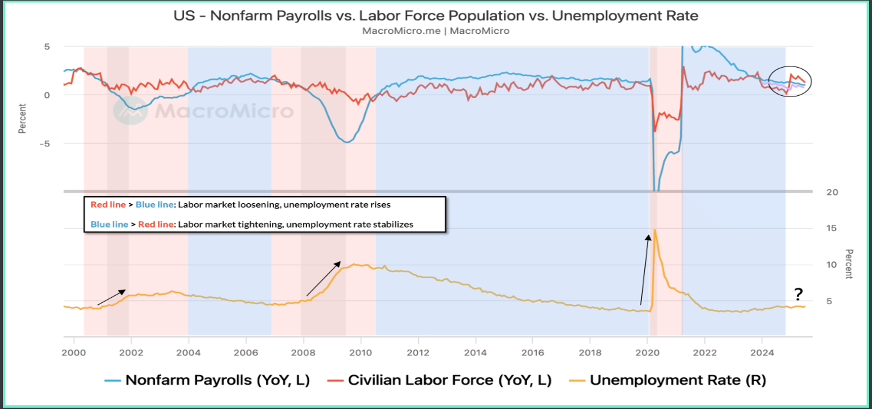

Exhibit 1: US – Nonfarm Payrolls vs. Labour Force and UR

How to Assess Labour Market Direction?

The unemployment rate essentially reflects both supply and demand and is therefore a key indicator watched closely by markets and the Federal Reserve. Understanding when and why unemployment begins to rise requires looking at the balance between these two forces:

- Tight Labour Market, Stable Unemployment (Blue Zone): When the US economy is stable or strong, labour demand growth (blue line: nonfarm payrolls) outpaces labour supply growth (red line: labour participation). In such periods, the unemployment rate (yellow line) typically stays stable or even trends lower.

- Loosening Labour Market, Rising Unemployment (Red Zone): When labour demand growth falls below labour supply growth, it often signals a sharp economic downturn. This imbalance leads to a looser labour market, layoffs, or business closures—causing unemployment to rise.

Is the Labour Market Currently in a “Fragile Balance”?

Currently, signs would point to the fact that the US labour market is in a state of “fragile balance”. Data shows that labour supply and demand are converging, with payroll growth (blue line) even slipping below participation growth (red line). Yet unemployment has not reacted—mainly because both supply and demand are falling simultaneously. This has created a delicate equilibrium where excess supply has not yet translated into higher unemployment.

In our view, while the unemployment rate has held steady due to the simultaneous slowdown in supply and demand, the underlying fragility of the labour market is rising. The Fed is therefore likely to focus more on sustaining labour demand, aiming to prevent an unexpected demand-side deterioration that could destabilise this fragile balance.

With fragility increasing, the Fed’s September 2025 rate cut is now virtually assured. CME FedWatch data shows the probability of a September cut hovering between 80–90%, even briefly exceeding 90%. We believe the current state of the labour market gives the Fed a credible justification to begin easing policy—without facing accusations of political interference. Such a move would be both understandable to markets and consistent with preserving the Fed’s neutrality and independence.

Going forward, the key question will be whether rate cuts can help rebalance labour market supply and demand, thereby supporting a soft landing for the US economy.