In the US, the UK, Japan and the Eurozone, central banks are buying government bonds in open markets. These bonds are in the market as a result of past government borrowing programmes, usually in the form of bond issuance, to finance budget deficits. Once upon a time central banks bought and sold bonds in what is referred to as “open market operations”, which expands or contracts the amount of money in the banking system. The central bank bought bonds and in return paid the seller cash. This cash would not be existing cash; the central bank would credit your bank account with newly created money and thus expand the money supply. It could conversely sell a bond, take that money out of circulation, at least in an electronic sense, and thus contract the money supply. In this way the central bank could change the amount of money in circulation and thus affect the economy.

Nowadays, central banks just seem buy to them and there is no sign of any selling. Some central banks have been buying bonds for so long, they own an awful lot of them. The US Federal Reserve, for example, owns about USD$2.5 trillion worth of Treasury bonds and USD$1.7 trillion worth of mortgage-backed securities (at face value). Bonds pay interest of course, especially when they are issued by a reputable government such as the US. When one holds a lot of bonds, one naturally receives a lot of interest.

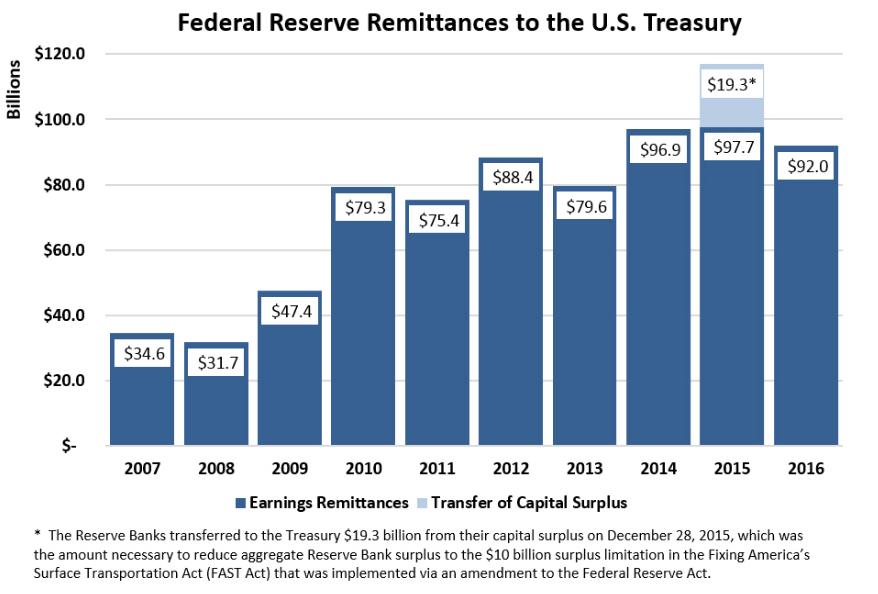

Just recently the US Fed released its income statement for 2016 and most of it came from the $USD111 billion it earned in interest from bonds it held, issued by the US Government. What did it do with this money? $4 billion went in operating expenses, such as Janet Yellen’s salary. $13 billion went in interest it had to pay to other organisations and private sector banks. $2 billion went in producing and “retiring” currency (that is, actual physical cash). The rest? Back to the US Government.