28 September 2015

The US personal consumer expenditure (PCE) price index is a little known economic statistic that is regularly released but rarely rates a mention. It has come into focus recently because the US Fed sees core PCE as its preferred measure of inflation and thus very relevant in the context of a looming Federal Reserve interest rate increase.

The headline PCE barely increased in August, in line with the median forecast of 0.0% and slightly lower than the July increase of 0.1%. The figures were released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis alongside the August consumer spending figures and they showed the index was 0.3% higher than August a year ago. The core figure, which excludes food and energy, was 1.3% higher and still below the Fed’s target of 2.0%.

28 September 2015

The long awaited 20 year bond futures contract made its debut on the Australian market this week and volumes were relatively light when compared to trading volumes in the longstanding 3 year and 10 year contracts. The new contract was first announced in May this year.

The Australian government had taken advantage of record low interest rates to issue long dated bonds out to 2037 and the Sydney Futures Exchange followed suit with the first new major bond contract in over 20 years. In May this year, the head of the Australian Office of Financial Management, Rob Nicholl, pointed to the body’s strategy of lengthening the government’s maturity profile in a move that has been warmly welcomed by the market. Long dated bonds and futures are seen as of offering better hedging and product pricing opportunities for life offices, insurers, mortgage providers and traders. The new 20y bond futures contract will trade under the code “XX”. For more information click here.

25 September 2015

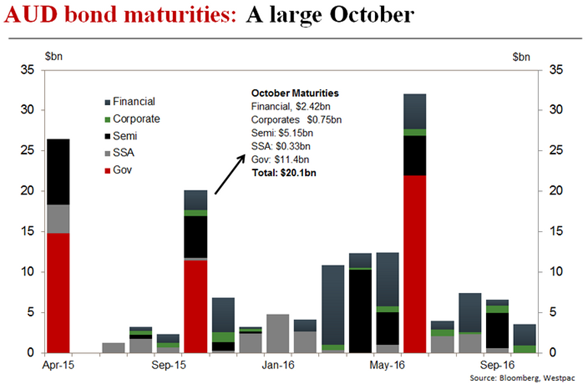

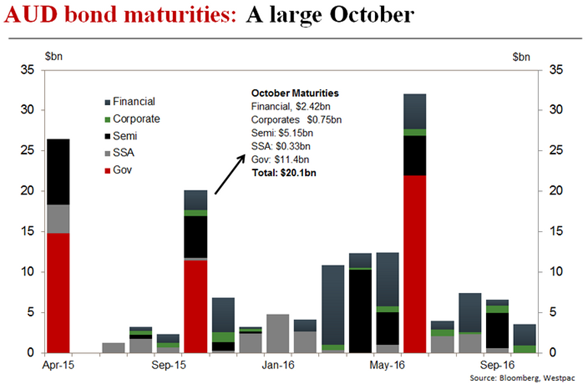

A large month for bond maturities is looming in October. Commonwealth and semi-government bonds account for over 80% of the $20bn of debt maturing in October. It’s not a seasonal thing either; the $4bn due in October 2016 is more in line with the $5-10bn which is due for repayment in a typical month. Regardless of the composition of the maturities, there’s a surge of funds to be transferred from government accounts to bond holders shortly and those funds will likely be looking for a home.

25 September 2015

The latest Taxation Office report on superannuation fund assets was released recently outlining where Australian super funds hold their members funds and changes from the previous update. At the end of June, cash and term deposits, loans and debt securities made up 28.5% of the average super fund, up from 27.7% at the end of the March quarter. Shares, unlisted and listed, dropped to 32.7% from March’s figure of 34.1% while property (both residential and non-residential) increased to 15.0% from the previous quarter’s 14.5%. The balance is made up of trusts, managed funds and “others”. For the full ATO report, click here.

25 September 2015

Bill Gross, one of the most well-known bond fund managers, is known for his regular pronouncements on the state of financial markets and the economy. In his latest missive, “Saved by Zero”, he has once again given us a smorgasbord of economic history, asset price theory and some plain common sense.

He says there is a price the US will pay for having zero interest rates and as zero rates become normal, “model-driven central banks seem not to notice” and that price will be higher the longer rates stay close to zero. This is “because zero bound interest rates destroy the savings function of capitalism, which is a necessary…component of investment.” He has two main areas of concern. The first regards companies which borrowed money at close to zero and then bought back their own shares rather than invest in the real economy, thereby defeating the central bank’s reason for having a low interest rate (ie: lend to business for productive purposes). The second is the effect on insurance companies and pension (superannuation) funds. Assumptions of 7%-8% investment returns which have held over the long term are not possible at the industry level with zero interest rates and both these industries depend on investment returns to fund insurance claimants and retirees.

So he has some advice for the Federal Reserve. “My advice to them is this: get off zero and get off quick.”

He says corporate America will suffer some pain in the short term but the benefit will in the form of rejuvenated private investment.

25 September 2015

Last week YieldReport reported on the RBA’s Guy Debelle comments to the Actuaries Institute Seminar in Sydney.

At the same seminar, APRA’s chair, Wayne Byres, gave a speech that implied some changes were coming which would ultimately lead to higher term deposit rates.

This is good news for term deposit holders that have seen TD rates slashed in the past 12 months and that have struggled to find alternative secure investments paying a reasonable yield in the face of extreme market volatility.

Wayne Byres told traders and investors that banks would need to change their balance sheets to prepare for new liquidity rules due in 2018. The APRA chairman said banks and other approved deposit-taking institutions still faced liquidity risks in spite of changes made to funding since the GFC. He also said overall leverage ratios had not really improved.

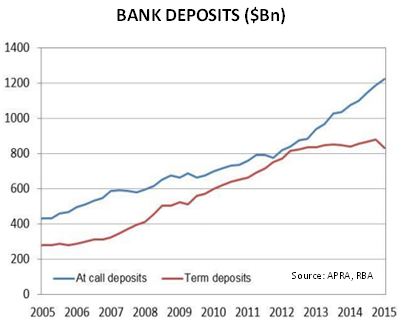

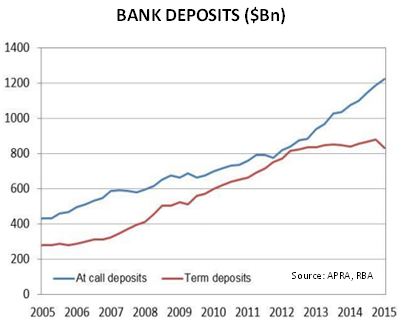

ADIs had pursued deposit growth to replace borrowing on short-term wholesale markets but the deposit growth has primarily come in the form of at-call deposits rather than term deposits. UBS said in a research note “Over the last three years the banks have been actively reducing their term deposit rates to help alleviate margin pressure.” At call deposits are less “sticky” than term deposits in the sense that depositors have easier access to them and could flee quickly in the event of a banking crisis. Post-GFC banks were fiercely competitive for term deposits, paying string premiums above the standard or ‘blackboard’ rate. Mr Byres said the lessening of competition for deposits, what he referred to as the “ceasefire” among banks when it came to competing for customers’ deposits, meant “liquidity profiles had been strengthened less than it might first appear.”

He went on to say ADIs had not materially reduced their reliance on offshore short-term wholesale funding which was typical of funding which was most likely to disappear in a crisis. As a percentage of total funding, this type of funding was “virtually unchanged” over the last ten years. “The largest Australian banks do not easily meet the new (“net stable funding ratio” due in 2018) standard” and further lengthening of Australian banks’ maturity profiles was probably required to “truly strengthen their funding resilience.”

As UBS put it: “APRA would like to see more term deposit funding … in our view the only way banks could achieve this is via higher term deposit interest rates.”

23 September 2015

Not so long ago, politicians were furiously point-scoring over how much debt was owed by the Federal Government. Which is curious, as the official figures are released each year in what’s officially known as the Budget Outcome. At the end of June 2015, total general government net debt was $238.7bn. It was lower than the May forecasts of $250.2bn and represents 14.8% of GDP. Net debt is equal to gross debt less assets, so there is room for debate as to what is included in the “assets” part of the equation and how the assets and liabilities are valued. For instance, as interest rates go down, the market value of the liabilities, that is the Commonwealth Government securities such as ACGBs, will rise although it‘s worth noting at maturity the market value will approach the face value. However, as long as the rate changes are not substantial, the changes in the amounts will be due to actual borrowings and repayments rather than market value changes. According to Westpac, in the eleven years to 2007/08, budget surpluses totalled $103bn but in the seven years from 2008/09 the cumulative deficits amounted to $277bn.

23 September 2015

RBA Governor Glenn Stevens and Assistant Governor Christopher Kent testified before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics as part of the RBA’s bi-annual report to Parliament. The RBA chief kept to what was described by Westpac as familiar themes such as global risks and the end of the mining investment boom but he also made mention of employment growth, a stable unemployment rate, the lower exchange rate and positive business surveys. Goldman Sachs said the prepared remarks did nothing “to suggest the RBA is positioning for another rate cut in the near term…”

In the Q& A portion the testimony two points emerged:

- The lower exchange rate is helping the economy re-adjust and “it’s hard to say that the currency is seriously mis-aligned.”

- Import inflation: a 10% drop in the exchange rate typically leads to an additional 0.25%-0.50% inflation each year for two years.

All of which led Westpac to say the cash rate would remain “unchanged for the foreseeable future.”

Perhaps the most interesting thing said by Mr Stevens was regarding the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy. “There will always be some weak data to say ‘don’t hike rates’, but one day you just have to do it.”

23 September 2015

BHP announced it was seeking to issue multi-currency hybrid capital securities and would be holding a series of investor meetings across Europe, the US and Asia beginning in late September. The non-convertible debt instruments would be issued by BHP Billiton Finance Ltd. and BHP Billiton Finance (USA) Ltd.

BHP said “The increasing interest in hybrid capital by global debt investors combined with the relatively low interest rate environment make this an opportune time for BHP Billiton to consider hybrid capital instruments.”

BHP has an A+ group rating from Standard & Poor’s and an A1 group rating from Moody’s. S&P said it had assigned an “A-“ long-term rating to the proposed hybrid issue. The securities would be classified as having “intermediate” equity content and thus qualify as 50% equity because they meet S&P’s criteria in terms of their subordination, permanence and optional deferment through a “call” clause. Moody’s has given the new hybrids an “A3” rating.

The effect of the part-equity classification means BHP can replace debt funding with hybrid funding and improve its gearing ratio all at the same time.

This would not be the first hybrid issued with the “part equity” classification. Origin, with its Origin Energy “Notes” (ASX code ORGHA) and Santos’ euro-denominated subordinated notes are examples of previously-issued hybrid debt which counted as 100% equity or partial equity for credit rating purposes. Click here more on the issues surrounding hybrid classification.

23 September 2015

At last count, there are over sixty preference shares, convertible notes and other hybrid securities listed on the ASX, so you’d think a hybrid reaching maturity would be fairly common. However, given the range of maturities, in practise it does not come up all that often. This month is one where a particular hybrid, Primary Health Care Bonds Series A, is approaching its redemption date. Holders registered on 18th September will receive a total of $101.55 on the 28th, comprising the $100.00 face value and $1.55 in accrued interest.