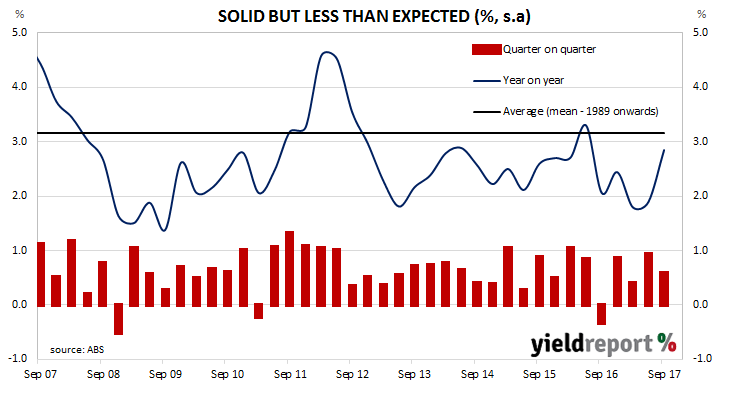

A recession is generally defined by economists as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP, an event which last occurred in Australia in 1991 which became known as “the recession we had to have”. Since that time, Australia has had the odd negative quarter, such as in the September quarter of 2016 and the March quarter of 2011, but not two in a row.

The latest figures released by the ABS indicated third quarter GDP grew by 0.6%, just under the 0.7% expected by economists. Even though the growth rate over the September quarter was less than June’s 0.9%, the year-on-year figure increased from 1.9% (after revisions) to 2.8%, which was also under the 3.0% figure expected.

Bond yields and the Aussie dropped on the release of the figures. 3 year bond yields finished the day 7bps lower at 1.96% and 10 year yields were 9bps lower at 2.53%. The local currency dropped from 76.15 U.S. cents to 75.85 U.S cents and then finished around 75.80 U.S. cents.