By Ken Atchison, principal, Atchison Consultants

How fiscal and monetary policy is conducted in Australia will be critical for its recovery from recession, which itself was driven by Australia’s response to dealing with the coronavirus. While a health crisis and an economic crisis were almost inevitable, avoidance of a financial crisis was a key policy of the Federal government and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). However, the RBA’s policy thrust has extended well beyond monetary policy.

In part, the Reserve Bank has been trapped into following the Federal Reserve, ECB and other central banks in keeping interest rates very low. If it I did not, the Australian dollar would have appreciated significantly. The notorious “Greenspan/Bernanke put”, the practice of the Federal Reserve cutting interest rates whenever US equity markets quivered, has had wide ramifications for more than two decades, and not just for the US.

Extreme actions have been adopted by the RBA as it imposes alternative policies. Having reached zero bound, lowering interest rates is no longer an effective policy tool. RBA Governor Lowe has stated:

- that the cash rate will stay at the low of 0.1% for at least the next three years.

- that preservation of states’ credit ratings is not particularly important. Creating jobs is much more important.

- that he has no concerns at all about state governments being able to borrow more money at low interest rates.

- that $100 billion of long-term federal and state government bonds will be bought over six months.

- that a $200 billion funding line of credit will be offered to banks to offer cheap money to business.

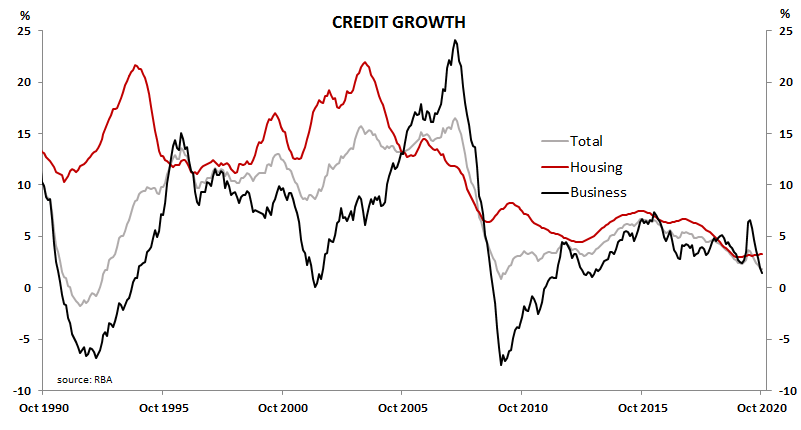

The RBA’s actions have only had a cushioning effect. Data to October 2020 indicates private sector credit rose only 1.6% in the year. Drastically lower interest rates have resulted in a minor increase in total borrowing for housing. Business credit is still contracting as survival is currently the business sector’s sole focus.

Lower interest rates and liquidity into the financial system has instead flowed into investment markets with housing prices not only stabilising but rising. Australia already has one of the highest levels of household debt-to-income ratios in the world; only four European countries have higher ratios.