Central banks want higher inflation. This has not always been the case. In previous decades central banks preached about the evils of inflation and how it diminished consumer spending power while it increased uncertainty regarding investment planning. However, all this changed after the GFC brought in fears of Japanese-style deflation and the “horrors” which came with that.

In recent years, almost every advanced economy has had extended periods where the various measures of inflation have been below central bank’s targets. Inflation figures above an annualised 2% have been rare and, on the occasion when they have been produced, there is not a great degree of conviction they will last.

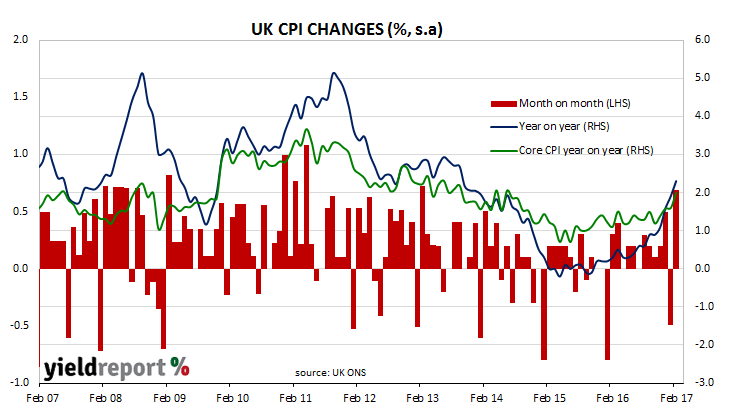

Perhaps the first of the advanced economies to produce inflation figures close to or at its central bank’s inflation target is the UK. Headline consumer price inflation (CPI) in February was 0.7% and 2.3% year on year. Core CPI, which is CPI excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco, increased by 2.0%, up from 1.6% in January.

Higher oil prices are partly responsible for the surge in the headline rate but it is the fall in the UK’s exchange rate after the Brexit vote which is viewed as the driver behind higher core inflation.