Overview

The good news first

Firstly, in relation to the corporate credit market, both investment grade and high yield bonds, to be clear we are not in a balance sheet / credit crisis. Fortunately, we entered this period with the underlying credit fundamentals broadly improving in the past couple of years as businesses and households hunkered down after the pandemic and benefited from supportive conditions. Rating actions have been balanced, refinancing activity has been robust, and the net negative outlook bias has been well below five-year averages—apart from a few tariff-targeted sectors and energy-intensive industries exposed to relatively expensive gas and power prices (such as in Europe).

Secondly, the credit markets have shown no signs of dysfunction. As violent as the price action has been, investors can take comfort from the fact that the microstructure of the market or the plumbing of the credit markets have held up very well. Relative to the moves during Covid lock-down period, it’s been very orderly. We haven’t seen any companies calling their banks and drawing down on revolver. Additionally, primary market activity has not seized up. While there has been a few days when primary deals were put on hold, this was due to volatility rather than lack of demand, as the case in 2020. This is not a Covid pandemic March 2020 period in which there was simply no buy bid on the offer and consequently high yield spreads blew out to 1,000 bps and CCC to 1,470 bps. And as a result, the Fed made the unprecedented move of buying high yield bonds. Because if they didn’t, high yield ETFs would have frozen redemptions. ETFs freezing redemptions – you do not want to even imagine the panic that would have gripped markets.

That’s the good news. Now for the identifiable downside risks.

Identifiable Risks

While things may be relatively orderly and all-in yields remain attractive, there are three major risks facing the corporate bond market now, and most notably in the high yield market and materially less so in the investment grade market.

They are:

- Credit spread widening as the market re-prices risk;

- Increasing default risk in the high yield market if the US / elsewhere heads into a recession.

- Downgrade risk, most likely due to earnings downgrade rather than balance sheet issues.

Credit Spread Risk

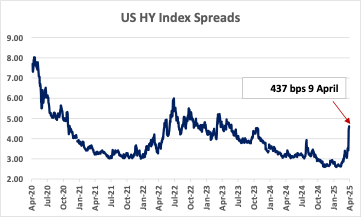

US investment grade corporates gained 0.28% over the course of the week while, not unexpectedly, high yield bonds declined -2.6%. High yield bonds extended a selloff Friday after China retaliated against US President Donald Trump’s latest tariffs and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signalled no hurry to lower interest rates. The extra yield investors demand to own high yield bonds over Treasuries widened a further 39 bps Friday to 4.24 percentage points. That’s the highest level since November 2023 and comes a day after the biggest jump in spreads since March 2020.

More significantly was the spread widening. U.S. high-yield corporate bond spreads surged to 401 bps as of late Thursday, their highest since November 2023. Widening in the US investment grade market was more orderly but still material rising to106 bps, the highest since August 2024, from 96 bps. For context, many believe spreads around 400bps indicate recession anticipation, and in 2022, amid peak concerns about high rates, spreads widened to 500bps.

For what seemed an eternity the corporate bond market was trading at historically tight spreads.This was based on strong fundamentals and strong technical. Regarding the fundamentals, issuers generally had / have strong credit metrics and ratings, low default rates, light refinancing needs, ample liquidity/cash in investor hands and supportive technicals more broadly.

In terms of the technicals, there has been a fundamental imbalance between demand and supply for years, most notably in the high yield market. The absolute size of the high yield market has not increased since 2015 due to the cannibalisation by the private debt market as well as leveraged loans market. At the same time, passive investment vehicles, notably high yield ETFs, have grown near exponentially.

It appeared nothing could break these dynamics bar an exogenous shock. Well, that came in the form of a grey swan event (a shock that is predictable in theory but largely ignored until it hits) in the form of Trump’s tariffs.

During the week ended April 4, 2025, the corporate bond market finally cracked, and particularly the high yield market.

U.S. high-yield corporate bond spreads surged to 401 bps on Thursday 3 April, their highest since November 2023. Widening in the US investment grade market was more orderly but still material rising to106 bps, the highest since August 2024, from 96 bps. For context, many believe spreads around 400bps indicate recession anticipation, and in 2022, amid peak concerns about high rates, spreads widened to 500bps.

Notwithstanding this widening, JPMorgan Chase & Co. warns that the high-yield bond slump is about to get worse due to the implementation of high tariffs on many US trading partners and a predicted US recession in 2H25. The bank’s strategists have raised their spread forecasts and made changes to sector recommendations, including increasing estimates on their proprietary gauge for the extra yield investors will demand to own high yield bonds instead of Treasuries.

JPMorgan increased estimates on their proprietary gauge for the extra yield, or spread, investors will demand to own high yield bonds instead of Treasuries to 550 bps by the end of the second quarter, compared to 459 bps on Friday. High-yield bond debt spreads ended Monday at 449 bps, the widest in 22 months. This follows UBS Group AG strategists now expecting corporate-bond spreads to reach levels last seen during the early part of the pandemic.

The strategists also widened their spread projection for investment-grade debt by 35 bps to 125 bps while noting their forecasts weren’t as dire as prior recession levels. As noted above, the good thing about corporate debt is it enters this period of slower growth with strong credit metrics and ratings.

Furthermore, JPMorgan raised concerns that the high yield market is papering over recession risks, with the strong technicals leading to passive investors (ETFs or maturity funds) blindly buying. On a historic basis, spreads are still in very good shape. Typically, a high yield bond spread of 800 bps is seen as presaging a recession. Even after the recent selloff, they are less than half of that on both sides of the Atlantic. A model by JPMorgan strategists showed in mid-March that the S&P 500 was pricing a 33% probability of a US recession, up from 17% at the end of November, while credit was only pricing in 9% to 12% odds.

Across credit, they recommend investors hide in sectors less likely to be hit by tariffs, including banks, domestic telecoms, health care, cable/satellite, utilities, railroads, tobacco, metals and mining as well as utilities. Portfolio managers are currently going through a bond-by-bond exercise to assess individual name tariff sensitivity.

Exhibit 1: ICE BofA US High Yield Index Option-Adjusted Spread

Default Risk

For starters, these developments mean that, probably without exception, economists have been downgrading recent macroeconomic forecasts. Credit conditions are taking a hit too. Financial markets have reacted negatively to the scale of the trade shock. This is likely to further undermine business and financial confidence, amplifying concerns around investment, employment, and growth. Furthermore, in our view, uncertainty will continue to weigh on growth prospects even after the pronouncement.

The worsening of global trade tensions, expectations for a global economic slowdown, and increased investor risk-aversion will likely affect what were previously expectations of a continued gradual decline in speculative-grade defaults. S&P states that this means defaults could trend closer to its downside scenario of 6% in the U.S. and 6.25% in Europe by December (compared with its baseline forecasts of 3.5% and 3.75%, respectively).

Historically, sectors that underperform in recessionary environments include CCC rated bonds (i.e., stay high in the ratings capital stack), debt from communications, consumer cyclicals , transports and basic materials sectors.

Ratings Implications

Rating implications may come from near-term changes in market conditions. But ratings houses will also consider the implications—positive or negative—of the longer-term reshuffling of global trade and supply chains that is at play for specific issuers, industries, and countries.

While we are not in a pandemic situation, as noted above, what the pandemic showed is how quickly ratings downgrades can occur. They came quick and fast in March, April 2020, and particularly on businesses in sectors particularly vulnerable to declining economic activity, such as the energy, and consumer cyclicals sectors.