Summary

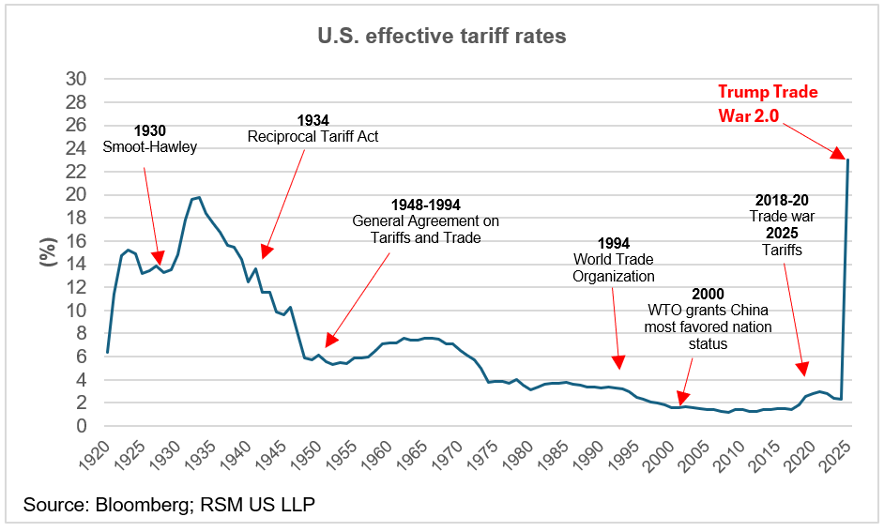

We have just witnessed the tariff announcement, and it was worse and more comprehensive than the market expected. Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research estimates that the tariff policy, coupled with other tariffs announced this year, will raise the US effective tariff rate by 18.8% – from 2.3% at the start of the year to approximately 21%, the highest level since 1910. Overall, the reciprocal tariffs exceeded market expectations in scale and scope and explains why the asset markets have reacted in the way they did. There was a big surprise factor, and economicsts and investors are slow and often inaccurate in their assessments of large policy interventions of this nature. The key issue is not just the direct or first order effects of tariffs but the subsequent indirect and second/third order effects that is very difficult to estimate.

Policy Sequencing

The Trump Administration is in the process of implementing significant policy changes in four distinct areas:

- Trade (tariffs),

- Government efficiencies (DOGE and less government regulation),

- Tax cuts (fiscal policy), and

- Deregulation.

It is the net effect of these policy changes that will matter for the economy (in the medium term) and for the path of monetary policy.

However, the impact of policy sequencing cannot be understated. The tariffs and lay-offs are required to fund the tax-cuts. It’s an exceptionally risky policy, a level of risk, apart the pathetic Liz Truss budget, rarely seen.

Already, the front-loading of regressive policies – higher tariffs and federal workforce layoffs–are disrupting economic growth and sentiment outlook relative to expectations of most investors and economists. The market has seen a slew of economists markedly downgrade US economic growth expectations and markedly increase the chance of a recession in the world’s largest economy. And that was before the Liberation Day Tariff announcements.. Post the announcement, more than a few are saying 50/50.

More worrying still, there is a risk of stagflation too, a worst possible outcome for the Fed and risky assets generally. If the Trump Administration is forced to pull back on the tariffs due to recession risks or stagflation, then how does the government fund the tax-cuts given the state of the US budget deficit? In other words, all pain and no gain.

Tariffs and Trade War

We have just witnessed the tariff announcement, and it was worse and more comprehensive than the market expected. Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research estimates that the tariff policy, coupled with other tariffs announced this year, will raise the US effective tariff rate by 18.8% – from 2.3% at the start of the year to approximately 21%, the highest level since 1910. Overall, the reciprocal tariffs exceeded market expectations in scale and scope and explains why the asset markets have reacted in the way they did. There was a big surprise factor, and economicsts and investors are slow and often inaccurate in their assessments of large policy interventions of this nature. The key issue is not just the direct or first order effects of tariffs but the subsequent indirect and second/third order effects that is very difficult to estimate.

The methodology of the tariff determination was completely unexpected – effectively they were set based on the US trade deficit absolute number with any given country and then, because Trump said he wanted to be nice, the figure was halved. Additionally, a minimum floor of 10% applied to any other country, which explains why Australia in which the US enjoys a trade surplus, was slapped with a 10% tariff.

Key Issues – the levels, structure, and trade goods coverage

Given the magnitude of the tariffs with no sight of an an exit ramp, the policy is rightfully expected to have economic growth consequences as well as inflationary consequences, although economists are very divided on the latter. The reaction of the US bond markets on Thursday, when the 10-year hit 4.0%, suggests the markets have very much focused on the former – growth prospects ahead of inflationary impact. This is because, if the economic growth slows, there will be some downward pressure of inflation simply due to aggregate demand falling. However, this line of thinking ignores the supply side shock to price stability as companies and producers re-price products and services and create short term inflation pressure even as aggregate demand falls.

Estimates suggest that the tariffs announced so far could reduce growth by 1-3% and increase US core PCE inflation by nearly 2%. However, the lasting macro and market implications will depend on various factors, including the duration of proposed tariffs, retaliatory actions, and fiscal support offsets (tax cuts) that may be unveiled in months to come.

In relation to inflation risks, a few quotes are worth noting in relation to core PCE, the Fed’s preferred measure:

- Michael Feroli, JPMorgan: “We estimate that today’s announced measures could boost PCE prices by 1-1.5% this year, and we believe the inflationary effects would mostly be realized in the middle quarters of the year”

- Peter Williams, 22V Research: “If one takes a now current policy baseline forward, core PCE forecasts for 2025 should be revised into the 4-5% range. The low-to-mid 3’s seemed appropriate based off policy this morning. Excess precision feels unnecessary and impractical. There is now going to be the feared second wave higher of core PCE inflation”

And there is many, many more, but they are all along the same lines.

Now the levels and structure has been announced, the critical issue becomes if there is an exit ramp. That is, to what degree is Trump using the tariffs as a bargaining chip and not a permanent trade policy setting. Only time will tell. If that is not the case, the markets, businesses, and consumers are likely to become deeply concerned about the direct and indirects effects of these policies on both economic growth and price level of goods and serices.

Government Efficiency – DOGE

Then we have the phenomena of the Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (aka ‘DOGE’). Trump has claimed that DOGE has already identified “hundreds of billions of dollars of fraud” and that Musk (if he remains in the position) will lead the charge to find US$1 trillion in savings by cutting government spending. DOGE is another headwind for the US economic growth – by signalling a reduction in government jobs and fiscal spending over the next four years.

The DOGE impact will have little reflection in the March Payroll data released on Friday, as the data collection point is still too early. But it will start to flow through in stats from the April onwards.

Finally, we have Trump’s executive order to reduce government regulations. This “Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation” mantra requires regulators to identify at least ten existing regulations for repeal when proposing a new regulation. Regulators must ensure that the net cost of all new regulations are “significantly less than zero.” This is a further example of the diminishing role of the US Federal Government planned under Trump.

Fiscal Stimulus – Tax Cuts

Meaningful fiscal stimulus via tax cuts is likely to arrive via budget reconciliation at the end of 2025. It is generally expected that the sunsetting provisions in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) to be extended beyond 2025. There is also the potential for a reduction in corporate taxes from 21% to 15% for domestic production.

The prospect of a big fiscal bonanza at the end of 2025 may prove to be a case of “better to travel than arrive.” Episodes of market stress linked to the administration’s economic agenda could be ameliorated by a few well-placed comments about the tax cuts that lie ahead.

However, once legislation has passed, investors – by then accustomed to the narcotic effect of promised stimulus – may find the comedown less agreeable.

In addition, while lower corporate tax rates may stimulate investment and job creation, there are questions about what tax changes would mean for the fiscal deficit. How much of the TCJA is extended will be key – a full extension of the TCJA could push the deficit higher. Separately – and importantly – how effectively tax cuts can drive growth will depend on the response from businesses and consumers, with potential implications for income inequality.

Deregulation

Deregulation – a broad-brush term – will likely vary by industry and company. Both US political parties have hinted at increasing regulation on big tech, particularly social media platforms. But in other areas, for example cryptocurrency and artificial intelligence, the Trump team wants to position the US as a global leader, suggesting less regulation in the sector.

Proposed deregulation, particularly in energy and financial services (bank capital controls), could lower compliance costs, potentially freeing up capital for investment and innovation. However, risks include potential environmental degradation and financial instability if traditional safeguards are weakened. The long-term growth impact hinges on whether deregulation fosters productivity gains and sustainable practices.