Summary: Melbourne Institute inflation index up in December; annual rate ticks up to 1.5%; implies large CPI rise in December quarter.

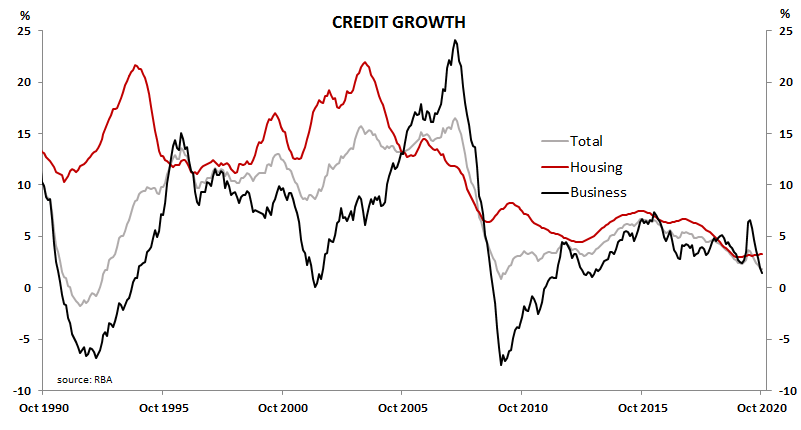

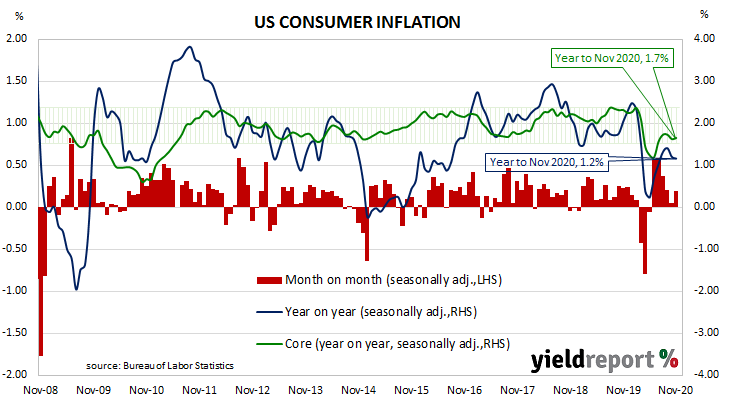

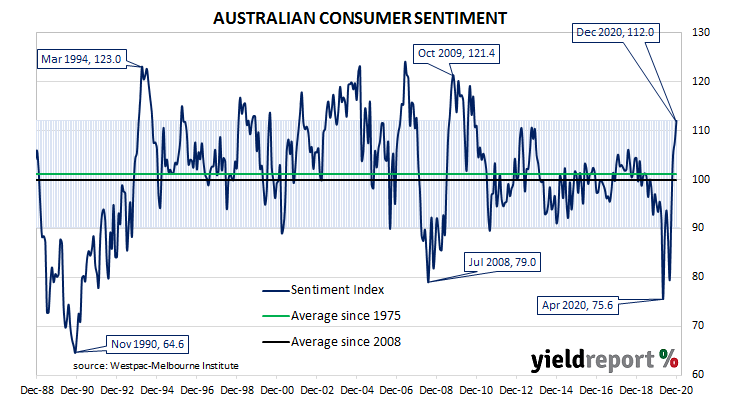

Despite the RBA’s desire for a higher inflation rate, ostensibly to combat recessions, attempts to accelerate inflation through record-low interest rates have failed to date. The RBA’s stated objective is to achieve an inflation rate of between 2% and 3%, “on average, over time.” Since the GFC, Australia’s inflation rate has been trending lower and lower; the “coronavirus recession” then crushed it in the June quarter.

The Melbourne Institute’s latest reading of its Inflation Gauge index increased by 0.5% in December. The rise follows a 0.3% rise in November and a 0.1% decline in October. On an annual basis, the index rose by 1.5%, an acceleration from November’s comparable figure of 1.4%.

Long-term Commonwealth bond yields fell modestly on the day, in contrast to somewhat higher US Treasury yields at the close of trading on Friday night. By the close of business, the 3-year ACGB yield had slipped 1bp to 0.19%, the 10-year yield had lost 2bps to 1.12% and the 20-year yield finished at 1.84%.

The Melbourne Institute’s Inflation Gauge is an attempt to replicate the ABS consumer price index (CPI) on a monthly basis. It has turned out to be a reliable leading indicator of the CPI, although there are periods in which the Inflation Gauge and the CPI have diverged for as long as twelve months. On average, the Inflation Gauge’s annual rate tends to overestimate the ABS headline rate by an average of a little under 0.1%.